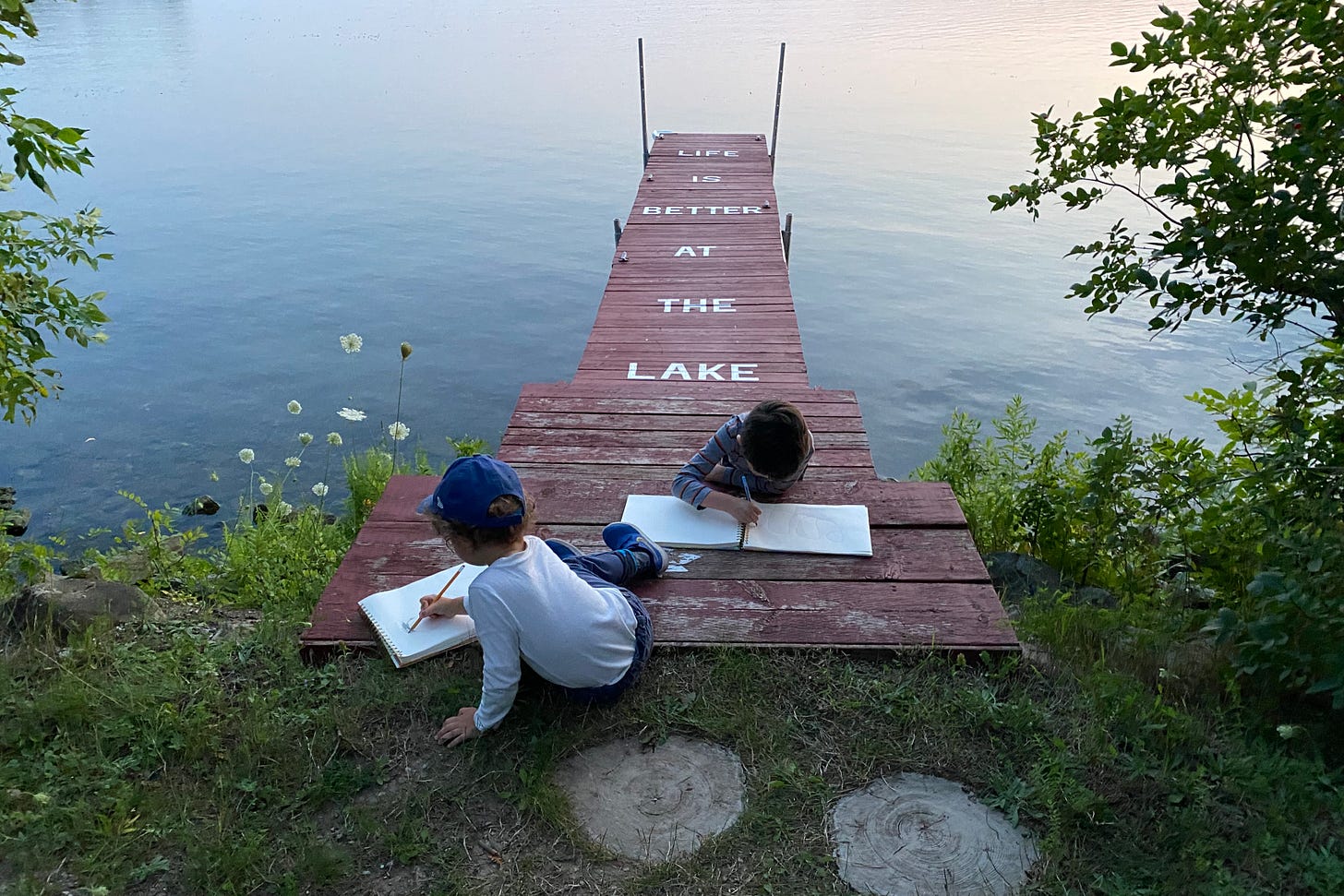

We took the kids camping this month, pitching our tent for four days right on the edge of Georgian Bay. We had good luck with the weather1 — no rain, few bugs, clear nights — and we all had a tremendous time, the kids most especially. They dug in the sand, swam in the lake, scrambled over rocks, tramped through woodland, admired sunsets, befriended chipmunks, roasted marshmallows, stayed up to watch the stars come out. The stars, in particular, were a revelation; both boys were quite overcome with awe by the starry night. In the days since, both of my little city mice have been in tears about missing “the country,” and asking to go back.

Then one day last week, I had a bit of a revelation of my own on the walk to school. We saw a cardinal dancing on the sidewalk, in all his red-feathered glory. Then one of the boys spotted a horse chestnut and wanted to know what it was. But sorry, no, we don’t have time to indulge your natural curiosity, watch cardinals, or learn about horse chestnuts, because I need to get you to school so you can do phonics worksheets2.

My revelation was that the boys don’t miss the country as much as they miss the unhurried time to just exist, without agenda or preoccupation. Parents are still busy while camping3, but we are busy with very tangible, logical things — putting up tents, building fires, fetching water, washing dishes. By contrast, the city agenda is almost always driven by abstract concepts like “9 o’clock” and “Powerpoint decks.”

This is neither more nor less than the eternal struggle of finite existence in a world of infinite possibilities. All we can do is be conscious of our priorities and deliberate in our decisions. But as my personal inertia is always towards too much Powerpoint and too few horse chestnuts, and I’m grateful for these small moments of reflection to recalibrate.

And on that note, this newsletter will be on summer hiatus for July and August. I’m looking forward to 3.5 weeks of vacation, making progress on my KPIs for evening-trips-for-ice-cream, and having time to watch the cardinals dance.

How Jobs End

There’s a weird disconnect in how we talk about jobs. On the one hand, it’s received wisdom that people will have many different jobs over the course of their careers (12–15 is the range normally cited). Average job tenure has been on a steady decline since at least 2010, and the most recent US BLS survey4 found that average work tenure has fallen below five years overall, and to 2.8 years for 25-34 year olds.

But in too many organizations, employers and employees alike tend to default to an outdated jobs-for-life framing. Employees feel like it’s verboten to talk about moving on, and don’t raise the topic until they tender a resignation letter with two or three weeks notice. Employers rarely provide advance notice about the organization changing direction and needing different skillsets, and they certainly never signal changing financial conditions until the layoffs have happened.

This status quo doesn’t serve anyone well. For employers, receiving two-to-three weeks notice is not nearly enough time to find and train someone to backfill a role. Employers are left scrambling, as are the teammates who have to cover on the now-shorthanded team. For employees, termination of employment comes without time to bolster savings, re-calibrate household spending choices, or job-hunt from a position of strength. (Ex-)employees are likewise scrambling, needing to come up with a new plan on short notice and often under great stress.

The Status Quo for Ending Jobs

When it comes to employee-initiated departures, you do see workplaces where the status quo is shifting. In these organizations, there is a lot of open and transparent communication about long-term career and life ambitions that extend beyond the current organization, and mutual trust that you won’t be penalized if you tell your boss you’re thinking of moving on. It takes a lot of hard work, a lot of manager training, and a lot of unlearning of old mental models to create that kind of culture. Even in those cases, there tends to be radio silence when it comes to interviewing and accepting a specific new role. But if an organization prioritizes creating a culture of trust and transparency around career progression and outside opportunities, I think you actually can get to a place where moving on is seen and as a natural and healthy part of the employee lifecycle, and the employer doesn’t focus on retention so much as proactive management of inevitable staff turnover.

When we look to employer-initiated departures5, it’s a different story. Outside explicit fixed-term contracts, it’s rare indeed for an employer to talk about a job having a shelf life6. Instead, we label jobs as being “permanent” full-time, while knowing they can be terminated at any time for any reason, or no reason at all. Employers don’t try to communicate clearly how or when a job might end, but instead focus their energies (and paperwork) to limiting costs and legal risk7 in the (not unlikely) event they need to terminate employment.

It seems to me that this approach is suboptimal on several fronts:

It disproportionately disadvantages anyone who is less familiar with corporate environments (typically employees who are younger, racialized, or working in lower-skill, non-union jobs), and therefore aren’t as well-equipped to navigate employment and termination negotiations.

It implicitly reinforces the notion that employers expect you to stay forever, and in that way undermines any organizational efforts to create more open and transparent conversations around career progression outside the organization.

It ignores the fact that many employees (especially younger ones) actively prefer jobs with 2–3 year tenures, and would choose to take on an assignment with a fixed horizon over one with an indeterminate length.

The absence of clear communications about how and why jobs might end compounds the uncertainty and fear around job loss. It also leaves an explanatory vacuum, which people who have lost their jobs are prone to filling in with their own deficiencies. As a result, job loss is more emotionally fraught and more bruising to self-confidence than it needs to be.

Setting new expectations for offboarding

Here is how I would love to communicate expected role tenure with new hires, right in their employment agreement.

Offboarding

While your job doesn’t have a fixed end-date, we bring employees onboard knowing they will move on to new opportunities. That might be a job in a different organization, entrepreneurship, travelling, or focusing on home responsibilities. You might choose to move on because you want to pursue a new opportunity, because of changes in your personal situation, or because the work of the company no longer fits with your career ambitions. Similarly, the company might choose to end your role because of a change in financial circumstances, or a change in direction or priorities that means we need different skills and capabilities.

We are very much looking forward to working together for a rich and rewarding few years. Right now, we are envisioning you working in this role in its current form for [x]–[y] years. But of course, no one can predict the future, and either of us might want to part ways sooner. Whenever it happens, we want your eventual offboarding to be a smooth, predictable, mutually agreed process with lots of notice on both sides.

If you are thinking about leaving your role

For your part, we want you to let us know when you are actively applying for other opportunities, or if you are approached for an opportunity that you want to give serious consideration. If we can, we’d love to help you find your next role, whether that’s making introductions, providing references, or something else. At these early stages, we aren’t asking for a firm end date, or even specifics about the opportunities you are pursuing, if you would rather not share. Our goal is to have enough advance notice so that we can plan for the future. Ideally, you keep us up-to-date through your process, so that we can accelerate (or decelerate) our contingency plans.

When you are ready to tender a formal resignation, we ask you to give us four weeks’ written notice. That longer notice period is intended to provide continuity for our business, and not to be a barrier to your pursuing new opportunities. Please don’t hesitate to discuss alternatives if the longer notice period is posing a challenge for you. Ultimately, we want to facilitate you moving into your next great adventure after a productive and satisfying stint with our team.

If we are thinking about ending or changing your role

If we decide we need to end or change your role for any reason, we equally want to provide you with ample notice so that you can plan for your personal and professional life. Our work lends itself to natural stopping points, where roles will need to end or change to meet changing client needs. Usually, those stopping points are foreseeable at least 3–4 months in advance, and we commit to having transparent conversations with you that weigh both the company’s needs and your career ambitions. Sometimes, however, business needs can change very quickly, because of unexpected developments with key clients or other external factors. In those cases, we might have to make such decisions on short notice.

In either case, we commit to giving you a combination of “working notice” (where you know your job is ending on a specific date, but continue to report to work to transition key tasks and deliverables) and “severance” (where you continue to receive your salary while not reporting to work). Under Ontario labour laws, as an employee, you are entitled to receive working notice and/or severance from any employer who ends your job. Typically, the amount of notice/severance you are entitled to depends on a number of factors, including how long you’ve been with the company, your age and experience level, and how long it might take you to find a comparable role elsewhere. We will strive to provide you with [z] months of severance, so that you have a financial cushion as you take time to seek your next role.

I would love to have language like that because it helps set the right expectations for the employment relationship. It’s clear and reciprocal, and also helps the new hire understand their rights. The only problem is it would cause any lawyer in a 10-mile radius to break into hives, because it exposes the company to too much risk in too many situations. The employer might still have informal conversations that convey the gist, but legal counsel will strenuously recommend new employees don’t get the clarity and peace of mind that comes from a written agreement that outlines what will happen in case of job loss.

I am not a lawyer and I don’t play one on TV, but I do think this is a problem. In other types of business agreements, the norm is to go into great detail about how and under what circumstances the arrangement might end. And in fact, when there is a more equal balance of power between employee and employer, we do see explicit agreements about compensation when a job ends. When employees gain power through a union, they negotiate contracts (like this one) with clear entitlement to generous separation payments8. When employees gain power by rising to executive-level roles, they typically negotiate severance clauses, specifying very generous compensation. We just deny those protections to the powerless, who need them more.

Changing this status quo is no easy thing. Probably, the existing legal-regulatory framework needs to be completely overhauled to be more reflective of modern work. But also employers need to recalibrate how they think about severance obligations, and employees need to educate themselves on their entitlements, and/or join unions that negotiate on their behalf. But it’s a sea change that’s needed, if we want fairness and transparency in how companies employ workers.

What I’m Working On

I’ve been doing some role design work for a client, and one of things we’re trying is designing two jobs to be a duo. That means the duo is collectively responsible for a set of outcomes for the business, and then the individual job descriptions outline how each role contributes towards those collective objectives. I just love this way of framing up job responsibilities — you have a built-in sounding board to build on your ideas, a built-in back-up who can cover vacations and sick days, a built-in pair of eagle eyes to give you feedback and catch your mistakes. Once you’re at a group of 3 or more, collaboration inevitably comes with coordination overhead (“Who is going to that meeting?” “Let me update you on that status…”). But duos can be wildly efficient, with the gains from complementary strengths and fresh ideas almost always outweighing the coordination costs.

It isn't much fun for One, but Two,

Can stick together, says Pooh, says he."That's how it is," says Pooh.

Especially in a hybrid or remote environment, I think the returns to staffing in duos are really amplified. Remote work can be lonely or isolating; having a built-in, go-to counterpart really helps with that. The second really valuable thing about a duo is how it forces you to think not just about the work to be done, but about the interactions and hand-offs that are necessary for progress. In divvying up everything from activities to KPIs, we are clarifying expectations within the duo, but also for how the duo will interact with the rest of the organization. Of course, you need high levels of trust and accountability within a duo, and it works best when the individuals’ skills and expertise are complementary. But that is true about any kind of ongoing collaboration. Creating structured, deliberate duos (whether at the level of a whole job role, or just a particular project) makes assumptions explicit and accountabilities clear, in ways we can easily gloss over if we’re just thinking about an individual. Even if duos at the level of full job roles is impractical in your world, I think it’s a valuable construct for projects and temporary assignments — who is your thinking buddy, how will you share responsibilities, and how will you support each other in the work that you do.

And with that, we’ve reached the part of the newsletter where I wish you all a wonderful summer. Have a splendid July and August, and I’ll see y’all back here in September.

In Comradeship,

S.

There was actually quite the windstorm for the first 24 hours. The tent was lifting up from its pegs and it had us a bit worried. But in the end, the only damage we suffered was full wineglasses being knocked over. That’s no joke when you’re in the middle of the woods, miles from the nearest liquor store, but we managed to persevere in the face of adversity. 🍷

In defence of the preschool, they are very creative and inquiry-based and let the children vote each week on what they want to learn about. Alas, I can muster no such defence of the public school, which seems to be mostly….phonics worksheets.

She said, by way of understatement.

These numbers probably overstate tenure, as they are from 2020, i.e. before the Great Resignation

I’m talking here about terminations without cause. Terminations for cause are thankfully rare, but would have to be handled differently.

The big consulting firms have a long had a 5-year up-or-out model, where associates know that many of them will be moving on within a fixed timeframe. Chief-of-staff roles increasingly come with a fixed time horizon and the expectation that the individual will move on to something else, whether inside or outside the organization.

For instance, an employer’s standard practice might be to pay generous severance that exceeds common law entitlements (usually about a month of severance for each year of service). They will nonetheless tend to have employment agreements that limit severance to the legal minimum (in Ontario, one week for each year of service).

There’s about 25 pages in this document covering job surplus, but on page 55 you see that employees whose jobs are eliminated are entitled to a lump sum of six months pay plus additional severance.

Thanks for sharing your thoughts on setting new expectations for onboarding.