Disconnecting March

Over-scheduling, an HR policy, and an epic birthday cake

Truth be told, March has been a bit of a struggle for me. Work is busy in that very hectic way where calendars are divided up into a dozens of little slices of interviews and meetings, such that you barely have time to think. The kids have been in-and-out of school because they are sick, because of March break, because their grandmother is visiting. Meanwhile, pandemic restrictions have eased and many social activities have resumed, leaving scant few evening and weekend moments that aren’t planned and scheduled. It’s a lot of logistics and time confetti, and it’s leaving me feeling discombobulated and over-scheduled.

Which, I guess, is as good an excuse as any to delve into disconnecting from work…

Right to Disconnect

As of June, new legislation here in Ontario requires all employers with more than 25 employees to have a written policy on disconnecting from work. For the purposes of the legislation, disconnecting is defined as:

Not engaging in work-related communications, including emails, telephone calls, video calls or sending or reviewing other messages, to be free from the performance of work.

The law is a bit funny, because it doesn’t actually create a right for employees to disconnect from work; it just requires employers to communicate their expectations in a written policy, even if those expectations are “be connected around the clock.” Workomics Inc. is exempt from the requirement, but I guess writing HR policies is my idea of a good time, because I’ve drafted one anyway.

And truthfully, I think writing a ‘Disconnecting from Work’ policy is a useful exercise in parsing the implications of modern knowledge work. So much of it can happen remotely and asynchronously, but there are also intense needs to be responsive and collaborative. These policies are of course specific to companies and their cultures, but I thought there might be some useful inspiration in how we’ve approached ours. Read on!

Workomics Disconnecting From Work Policy

At Workomics, we view disconnecting from work as not so much a right as an obligation. First and foremost, this obligation is to yourself. There is more to life than work, and we want you to disconnect so you can nurture all the interests and relationships that help you flourish as a human being. Empirical research suggests you’ll get the most benefit if your disconnected time includes things like exercise, the great outdoors, new experiences, service to others, and deep connection with the important people in your life. But ultimately, prioritize whatever brings you joy.

Disconnecting from work is equally an obligation to the business. It is essential to doing your best work, in two complementary ways:

Disconnect from work: Take breaks and rest. Being ‘always on’ has negative effects on your concentration, your creativity, and your productivity. Over the long run, it will have negative effects on your physical and mental health. You should disconnect regularly during the week and over weekends, and take vacations where you’re so disconnected you almost forget work exists.

Disconnect to work: Email and Slack are not your job (even if it sometimes feels that way). Book your calendar so you have multiple blocks per week when you can disconnect for at least two consecutive hours and focus without distraction. Your work will be better for it.

In sum, we have a deep philosophical commitment to disconnecting. It’s not something we do because of government fiat; it’s something we do because it makes our work better, our people happier, and our business more resilient.

Expectations to Connect

Before we can outline expectations on disconnecting, we first need to define its inverse: expectations for being connected. Most of our work is remote and your colleagues and clients are scattered across North America. The shape of the work changes day-by-day: sometimes it calls for independent heads-down time, sometimes it requires high levels of responsiveness, sometimes it demands intense collaboration. We could make up a system of core hours where we expect everyone to be online and available, but that seemed like it would be needlessly rigid and bureaucratic. Instead, our policy is simply this:

You should be sufficiently connected so that your availability and responsiveness does not impede your colleagues’ productivity, the quality of your work, or the satisfaction of your clients.

We are keeping the policy simple because we want to afford everyone maximum autonomy and flexibility to work in the ways that are most effective for them. For the policy to work, it requires everyone to abide by three principles:

Communicate

Anticipate

Reciprocate

Principle 1: Communicate Availability

With the ability to set your own hours comes the responsibility to communicate your availability. Everyone you work with should know your work schedule and your connected times, and there should be no surprises about your responsiveness. Tactically, this means the following:

Your calendar should be an accurate representation of your availability, at least a month into the future.

Enable the ‘Working Hours’ feature to set your standard schedule, and block any times you are unavailable within that (whether it’s a dentist appointment or heads-down time).

Don’t rely on your calendar to passively communicate availability out of the ordinary. Whether you’re taking vacation or logging off early to teach BodyPump, make sure you put it in your calendar and tell people.

In your #daily_async post on Slack1, let people know what to expect from you in terms of connectivity. Throughout the day, update your Slack status so that people know whether you are available, and when they can reasonably expect a response.

When you start a project (or even a new project phase), have an explicit conversation about things like preferred channels and expected response times.

Principle 2: Anticipate Others’ Needs

You are not the only stakeholder in your schedule. Your colleagues and clients have objectives and priorities that depend on your availability, and your connectedness should reflect that. If you are in Toronto and your west-coast client has a key deadline at 5pm PT, it is not okay to simply say, “I disconnect after 5pmET/2pm PT, so it’s not my problem.” That doesn’t mean the only option is for you to personally be connected until 8pm ET. It does mean that you should anticipate the potential need, and communicate a workable solution in advance.

You should bring the same mindset to collaboration with your colleagues. If there is a deadline on Thursday, you shouldn’t plan to be disconnected on Wednesday. If you have a non-negotiable personal commitment on Wednesday, then you should anticipate the potential crunch and work with your colleagues to move the crunch earlier in the week. Nobody wants you to miss your mom’s birthday/curling league/kid’s school play/comic convention. But equally, nobody wants to be stuck picking up your slack when some advance planning would have let the team share the load more equally. Ultimately, it is incumbent on you to anticipate how projects and deadlines should shape your availability. If you’re unsure, be proactive in discussing potential conflicts.

Finally, an important part of this principle is anticipating your colleagues’ schedules and adapting accordingly. Schedule emails and Slack messages to arrive during their normal work hours. Don’t book over a heads-down working block without asking permission. Don’t ask them to do something before end of day if their day is supposed to end in 20 minutes. Make recordings and detailed notes to facilitate asynchronous catch-up. You won’t anticipate perfectly every time, but if we are mindful of others’ schedules it will be easier for everyone to disconnect and reconnect seamlessly.

Principle 3: Reciprocate Flexibility

No matter how carefully you communicate or how thoughtfully you anticipate, there will always be unexpected surprises: the last-minute fire-drill from your client’s boss; the colleague who fell ill and can’t deliver as planned; the task you thought would take 4 hours but actually takes 28.

When those unexpected surprises happen, we expect you to reciprocate the organization’s flexibility and find workable trade-offs so we can still meet our commitments. To be clear: that does not mean we expect you to cancel your personal commitments every time something pops up. We do expect you to be creative and flexible in looking for solutions, and that sometimes you will make reasonable concessions to your planned work schedule.

The key thing here is that we want this to be a give-and-take relationship. If we afford you every flexibility in setting your own schedule, and you meet us with rigidity when something urgent crops up, then that’s just take-and-take. Our line of work doesn’t require us to keep fixed hours, but the flip side is it will never be fully predictable. We need everyone to have a mindset of flexibility, or the whole system breaks down.

Equally, the whole system also breaks down if we are constantly asking for individuals to deviate from their desired schedule. In order for flexible scheduling to not be a sham policy, the scheduling concessions you make should be proportionate, equitable, and rare:

Proportionate to the business need: Cancelling a vacation is not proportionate; working on a Tuesday night when you didn’t really have other plans probably is proportionate. The goal should be to find ways to mostly satisfy the business need while minimizing personal imposition.

Equitable between colleagues: It shouldn’t be the same people stepping up every time. It might make sense for the non-parents to raise their hands for things that have to happen during daycare pick-up. It might make sense for west coast people to take more of the late nights. But if that translates to the same people always shouldering any extra load, that’s unfair and we need to find a way to rebalance the scales.

Rare: Given the nature of our work, you can reasonably expect to have to make concessions on your personal plans perhaps four or five times a year2. If it’s happening more often than that, the first step is to see if improved communication and anticipation can help. If not, then it’s a problem, and we’ll sit down to find a solution.

The bottom line on flexibility is that if you don’t feel like you can routinely plan to be disconnected without work interfering, that’s a sign that something is broken and we need to fix it. If you occasionally need to adjust some aspect of your plans because something unexpected and urgent has come up, that’s a sign the system is working as intended.

Some Practical Guidance for Phones

Thirty years ago, disconnecting from work was easy. Work happened in a specific place at specific times, and you disconnected by just…leaving the building. But now, we stay in the same physical place and use the same device for work that we use to watch shows, listen to music, message the kids’ school, pay bills, make a restaurant reservation. It can be really hard to follow-through on our own intentions and actually stay disconnected. But we really, really want you to disconnect from work for significant chunks of every day, over the weekend, and especially on vacation. So here are a few non-mandatory suggestions for keeping yourself disconnected from work

Don’t install Slack on your phone. Slack messages can feel like a constant onslaught, and the dopamine hit from checking the messages can be so hard to resist. We would really encourage you to treat Slack as a desktop-only tool, that you use during your planned/scheduled work time.

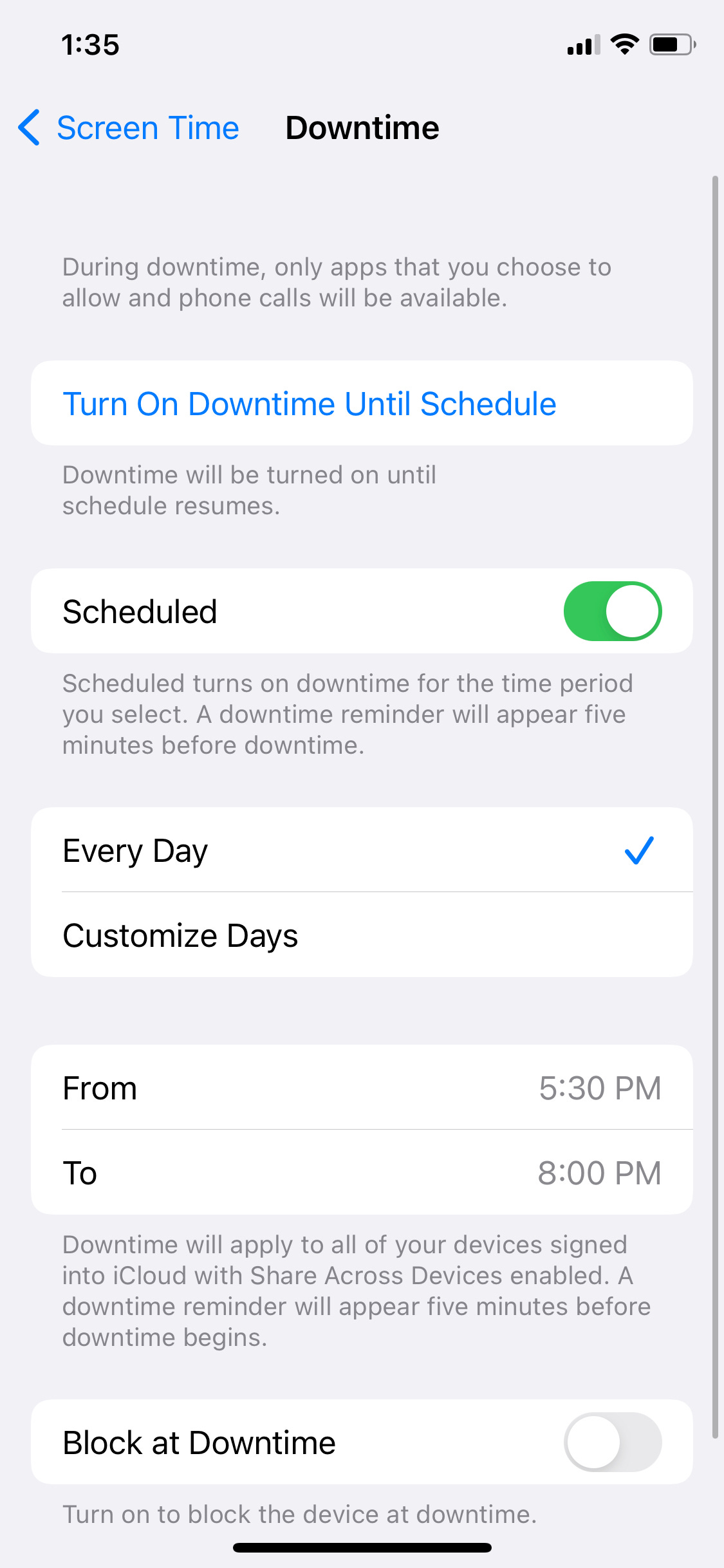

Make use of your phone’s built-in ‘disconnecting’ functions. On iPhone, it’s called ‘Downtime’ in Screen Time. On Android, it’s called ‘Focus Mode’ in Digital Wellbeing. Both of them allow you to schedule times when certain apps aren’t usable and don’t send you notifications. Use it for your email, and anything else that sends you notifications that might pull your attention back into work, and let people know they should call you if there’s an emergency.

Disconnect your work email when you are on vacation. With most phone-based email clients, it’s a simple operation to disconnect your work email when you leave on vacation, and reconnect it when you come back. That means you can still email trip photos to your friends, and not get sucked into the work vortex.

What I’m Working On

Blah, blah, blah stakeholders, strategy, customer experience, blah, blah, blah. What I really worked on this past month was cake. A whole lotta cake.

My youngest turned four at the end of March, and for the first time since Covid, we actually had a party with a few of his little friends. A birthday party, obviously, requires cake. You could buy a cake, or make a cake in the shape of a circle.3 But ever since they visited the aquarium last fall, my kids have been enthralled with all things shipwrecks, so I had the bright idea to make a Titanic cake. As in, a cake shaped like Titanic.

It was quite the undertaking. I legit spent most of the month of March working on it, between the planning, the baking, and the final construction. There were four different cakes:

A yellow layer cake with fudge frosting as the hull.

A chocolate butter cake (also from Sky High Cakes), with a raspberry filling and a vanilla buttercream, to serve as the superstructure

I made the funnels with the same yellow cake batter, baked into ladyfinger tins and sandwiched together with fudge buttercream.

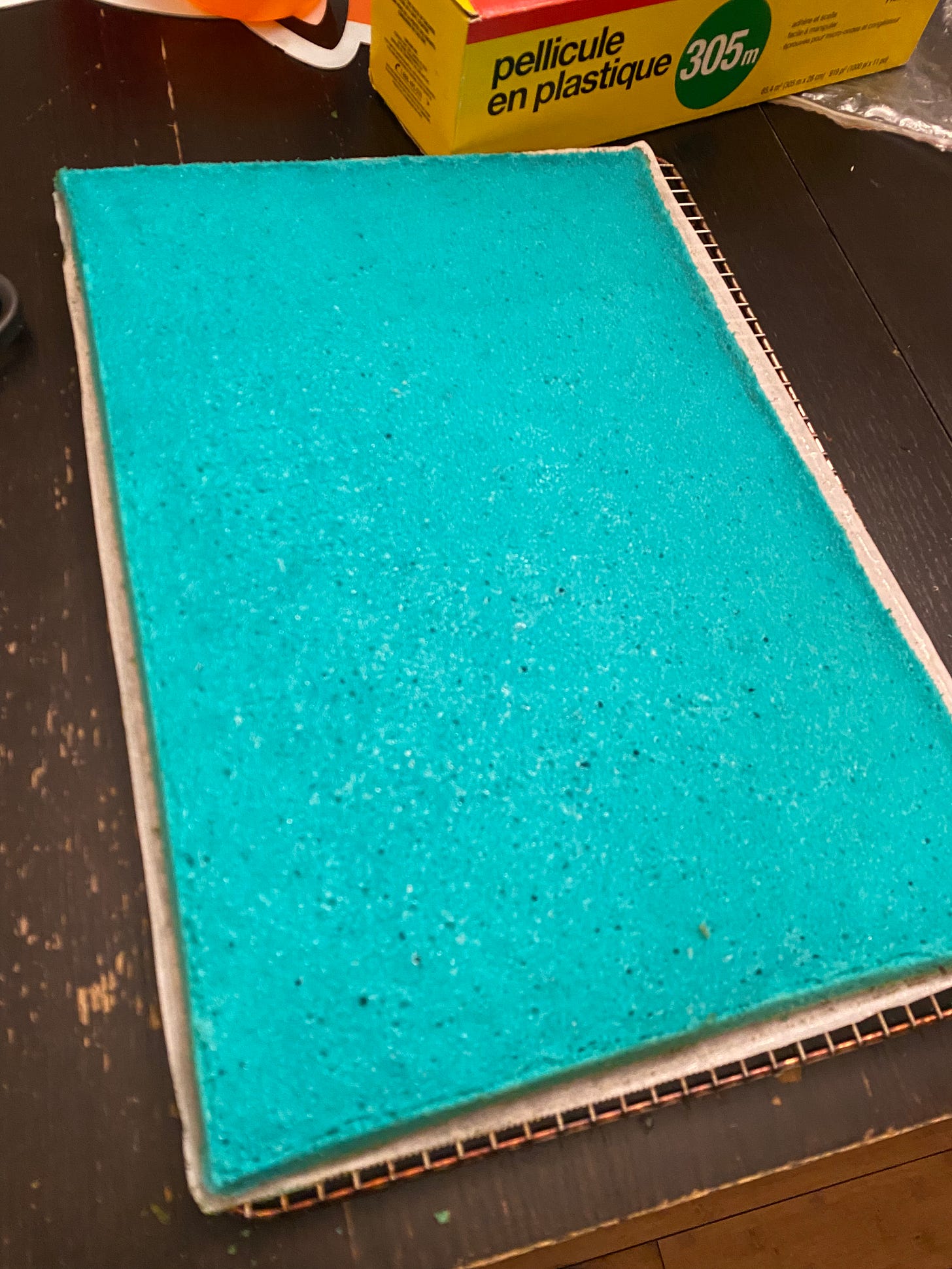

A vanilla butter cake (from Sky High Cakes), with some blue food colouring to be the ocean. Originally I planned to make a blue mirror glaze to go on top, but I’m glad I walked away from that4.

A confetti cake with blue sprinkles and vanilla buttercream to be the icebergs.

I baked the cakes in the weeks leading up to the party, storing them triple-wrapped in the freezer. On the day before the party, I carved the cakes into shapes, and then on the morning of, I assembled all the pieces together. Here it is, all assembled:

I am really pleased with how it turned out, both in look and taste. The newly-minted four year old was beyond excited,5 and his sheer delight made it more-or-less worth it.

But it was an awful lot of work.

The astute observers among you will draw a straight-line connection between my feeling over-scheduled all month, and my overly-ambitious month-long baking project. You are not wrong to do so. And that is the eternal struggle, isn’t it? To fit in all the things we want to do, between work and friends and family, while not feeling crushed by the relentlessness of it all. A ‘disconnection from work’ policy does not come close to solving for that. But hopefully, it helps people draw clearer lines around work, and be a bit more accurate in calibrating their ambitions, energy levels, and available time. Certainly, that will be my goal for April.

In comradeship,

S.

This is a bit inside-baseball, but we have a daily ritual of each person posting on Slack something that’s part stand-up and part water-cooler talk.

Again, these are proportionate concessions, so we’re not talking about interrupting your vacation four times a year. We mean working on a deliverable on a Saturday, or logging back in when you get back from your evening plans.

I want to be really clear that I think buying a cake at the grocery cake is a really excellent way to cater to a kids’ birthday party. But much as I am the kind of person who writes HR policies for funsies, I’m the kind of person who undertakes overly-ambitious cake projects as a lark, and in neither case am I advocating that as a sensible choice for others. Indeed, if anything, you should learn from my example and do otherwise!

Because of course it was the *mirror glaze* that would have taken the whole project over the top. 🙄

Ever the pedant, his older brother pointed out that they wouldn’t have written ‘RMS’ on the hull, and that I should have made yellow portholes on the hull. He is, of course, right on both counts. Also, he wants me to make a cake-based SS City of Benares for his birthday in May, which, I can’t even.